“Here is the pièce de résistance!” says Dennis, our guide at Arizona’s Hull Mine in Castle Dome City. “Follow me!”

“Sounds great, looking forward to this!” I reply.

Our group follows him down another mine shaft to where it opens up into a small room with a ceiling that is about 55 feet high. There is a narrow tunnel off to the left, and it’s definitely not wheelchair accessible down there.

“Now put some goggles on as the light can hurt your eyes without them.” Dennis tells us. “OK, now I’ll turn on the lights.”

First the cave is darkened by extinguishing the regular lights, then the ultraviolet lights are turned on. There are several pointed in different directions to illuminate the cathedral.

“Things should light up soon,” Dennis assures us. “It’ll take a few minutes to charge the rocks.”

The Invite

We are 100 feet below the surface in an abandoned silver mine that has been made safe for public viewing by shoring up the walls and pouring a concrete floor throughout most of it.

Our adventure started a few days ago when our wives went down into the mine on a tour. We were told it wasn’t wheelchair accessible, so my friend Jim and I opted to take one for the team and enjoy the desert sun in the parking lot. While leaning back, doing our best impressions of a lizard, a gentleman rode up on his bicycle and stopped to chat.

“You boys enjoying the sun?”

“Yes, the rest of the crew is on the tour, we stayed here,” Jim replied.

“If you could get to the entrance, we could probably get you down, it’s paved all the way,” he says. “Can you get transferred into an ATV?”

“Not easily, but if my van could get to the mine, I might be able to go down. What’s the road like?”

“About the same as the last few miles of gravel that you came on. If you want, we’d let you drive to the mine sometime to see. The shaft is about a 16% grade — can your chair handle that?”

My inner voice is nattering, “Pshaw, my buddies and I have tested my chair on stuff way steeper,” but my senior judgment auto-corrects my words before they hit my mouth (a relatively new skill): “We might just be able to make it.”

“Do you work here?” I ask.

“Sort of,” he says. “I own the place.”

And so here we are, a few days later on a private tour with Dennis, a volunteer guide at the mine. The trail to the mine was about a mile long, winding up and down desert gullies — nothing that the minivan couldn’t handle.

Inside the Mine

“I can see the colors — the rocks are starting to glow,” I say.

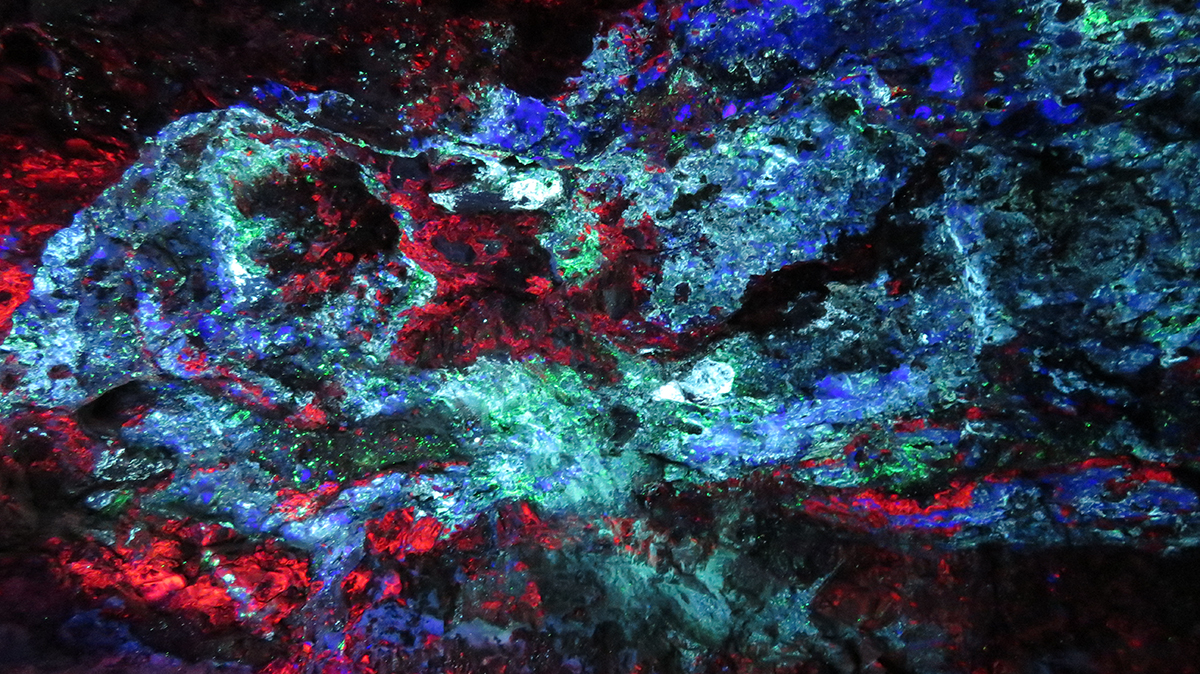

Under ultraviolet light, you can start to see reds, greens and blues from the walls of the cavern. Within a few minutes, the colors are so vivid it looks like there are lights inside the walls. I lean my chair back and discover the colors extend way up.

“What causes this?” I ask.

Only 600 feet below the hot Arizona desert lies the stunning fluorescent mineral cave wall.

.

“The minerals in here are phosphorescent. They seem to charge up in the ultraviolet light and then emit these fantastic colors. This place is kind of an anomaly, rocks that phosphoresce aren’t that rare, but most stop glowing shortly after the light goes out. In here, they will emit light 20 minutes or more after the lights are turned off. We don’t know of another place where this happens.”

Once we are done taking pictures, Dennis extinguishes the ultraviolet lights. Sure enough, the walls continue to glow, and when we leave 20 minutes later the light from the walls is still visible.

On our tour we saw a cavern that was once used as a hideout for outlaws. Apparently, they were relatively safe in there, as lawmen had little interest in entering a cramped mine and being greeted by heavy fire-power. At one point a bat emerged from a tunnel and fluttered around before returning. There are hundreds of bats down that shaft, which we were told is about a half-mile long. It is normally closed off during tours. There was a silver vein plainly visible in the ceiling, and old artifacts found down in the mine such as tools, chisels and hammers — almost like the miners walked out after their shift and never returned. The museum even has a pair of Levi’s jeans from the 1800s.

There was a “two-holer” rail-cart biffy held in place by a bar and chain under the wheels. The word is that when a new worker sat on it to relieve himself, a veteran would pull the chain to release the cart down the track giving the new guy a fast pants-down run through the mine. Apparently, the term “Don’t yank my chain!” came from these adventures.

It was well worth the fee to go down in an abandoned mine, especially in a power wheelchair.

Frequently Asked Questions

How steep is the grade?

I heard it was 16%. With my Quickie 646 power chair I simply leaned back to move the center of gravity and wheeled slowly down into the mine with help hanging on behind. It is up to you and your crew to determine if it is passable for you in your situation. Personally, I have gone far worse places with this chair, but that doesn’t guarantee that on some of my adventures sound judgment was always utilized … or even available!

Where is the mine located?

It is between Yuma and Quartzsite, Arizona. You travel north of Yuma on Highway 95 to mile marker 55, then turn east for 10 miles. The last seven miles are gravel, but our minivan had no trouble. Just leave extra time so you’re in no hurry.

How far down is it?

The journey down the tunnel is about 650 feet long and drops about 100 feet down. It was comfortably warm down there.

For more information, visit www.enchantedcavern.org.

** This post was originally published on http://www.newmobility.com/2019/06/mine-all-mine/