Illustration by Mark Weber

Illustration by Mark Weber

Your parents are getting on in years. They’re definitely slowing down and in need of an occasional hand, a need that will likely only increase with time. They were there when you most needed them, and now it’s your turn to be there for them. This may be the most difficult thing you’ve ever done for someone else. But you’re not alone.

NEW MOBILITY reached out to four wheelers who have dealt with different issues around caring for aging parents while also caring for themselves and others. Here is what they learned.

Advising and Supervising

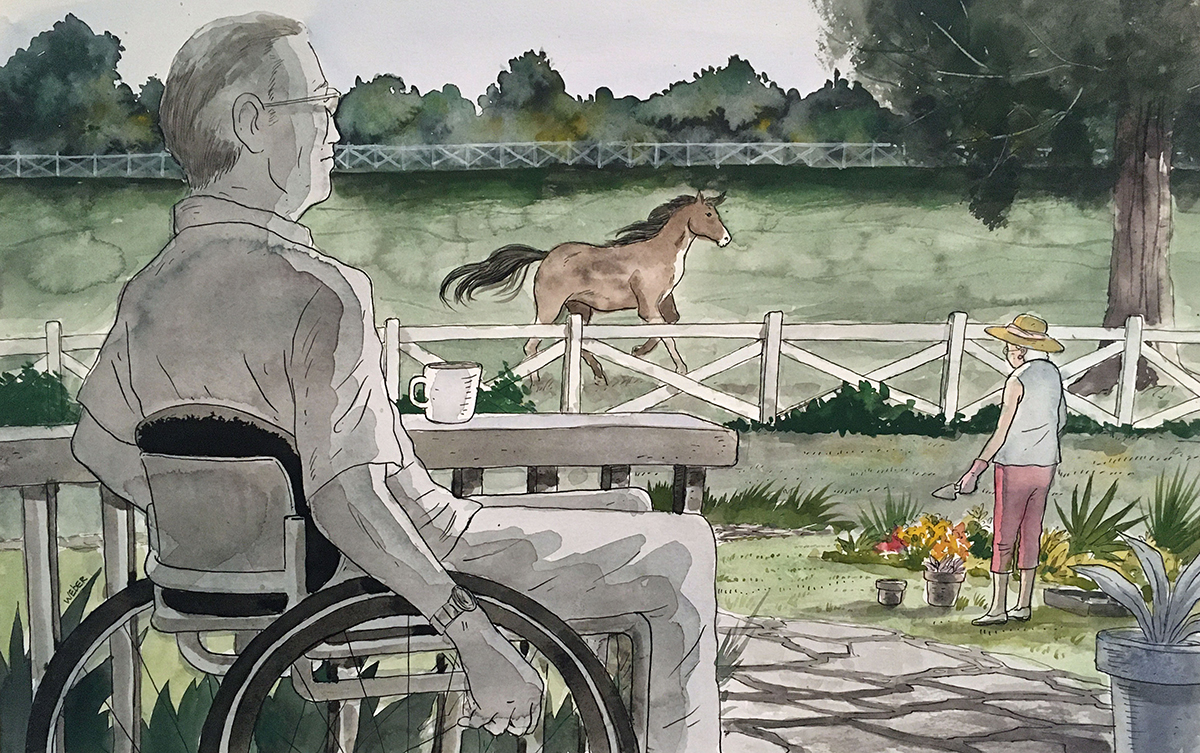

Christopher Finney, a 65-year-old para in rural Kansas, manages to keep an eye on his mother as best he can. Finney owned an electrical business with his father prior to being knocked out of his truck’s bucket and falling 27 feet. “I didn’t bounce well,” he deadpans. “After dad passed, Mom and I owned the business, and she’d use me as a sounding board. That’s when I noticed her repeating herself a lot.”

They’ve since sold the business.

“The problem is my mother is 85, extremely headstrong and often unaware of having any problems at all,” he says. “Or at least she never mentions any problems. Needless to say, I spend a good deal of time at her place, advising and supervising.”

He talks with his mother every day and visits weekly to get a feel for what’s going on in her life. “She’s been making some poor decisions lately,” he says. One of her poorer decisions was not calling him for help when she needed it. “She fell, but failed to activate her medical alert device, not realizing she didn’t purchase the automatic alert feature. She was angry, thinking it didn’t work. Now she refuses to wear it. She also had her cell phone but didn’t call my wife for two hours because she didn’t want to bother us.”

Another poor decision was buying a colt.

She’s ridden her entire life, but pain, followed by surgery and then a broken ankle, has left her too weak to saddle and mount a horse. So the colt is a big pet that is beautiful to look at in the pasture and fun to watch play. Besides, she has two other horses she can ride.

“Now I worry about her getting kicked or hurt some other way. I spend a good deal of time worrying about her health, as well as my own. Frankly I’ve been surprised at the degree of her mental decline,” he says. “Obviously the situation is stressful. I’m always talking to her, listening to her, monitoring what she says, watching her decision-making and trying to get a feel for what’s going on. My mother’s not exactly totally forthcoming.”

All of these issues make it hard for him to look ahead at the future discussions he knows are coming, should her decision-making worsen.

Though Finney has two sisters, they offer little support, leaving him to deal with the situation. “I’m very fortunate that my wife is so supportive. I could not care for Mom without the help of my wife, aunts, uncles and a large circle of friends,” he says, but in the end, her care falls to him. “Physically it is very frustrating trying to help her. If she falls, I can’t help her up, and I can’t get into her home without assistance. When she had an allergic reaction to medicine and suddenly began having difficulty breathing, I rushed her to the local ER, but all I could do was honk the horn until help came. If this had happened when she was alone, she would probably not be with us now.”

Finney wishes he could do more. “I feel daily frustration in my inability to give the physical help she needs,” he says. “It’s emotionally draining because sometimes I have to put my needs first. She has always cared for others — especially me since my injury. I feel guilty because if I had not gotten hurt, both our lives would have been so different. My parents made sacrifices for me my entire life, especially after my injury, to improve my quality of life.”

Finney focuses on the positives in his situation. “We’re spending lots of time together, as well as time with her sisters and brother, sharing meals and conversation. She may tell them things that she hasn’t told us. They’re very helpful and sometimes are a good source of information regarding her health,” he says.

COVID-19 has added an extra layer of concern, but during the shelter-at-home period, Finney continues to contact his mom daily to care for her physical and mental health. “My wife supplies her with books to read and picks up her groceries,” he says. “We still get together to share meals and play dominos several times a week. Mom feeds her dog, cats and horses daily. It gets her outside in the sunshine and fresh air.”

Even with the difficulties, Finney recognizes the fortunate position he’s in. “I feel honored to have an opportunity to repay the love and devotion my Mom gave me. To be able to help her, now that she has needs, gives me more purpose each day.”

Tangled Up in Knots

In October 2018, Joe Jeremias’ 70-year-old father had a massive stroke and now is a hemiplegic. After three months and some rehab, he was sent home to live with his wife, also 70, in his inaccessible house.

Prior to his discharge, a social worker asked Jeremias’ mother what kind of help she would need. She said none — that she had two sons who live nearby, and one of them didn’t work that much. Jeremias, who she didn’t mention because he lives three hours away, is the third son, a C5 quadriplegic for the past 33 years. His mother then assumed the role of his father’s sole caregiver, mostly due to “pride and her stubborn nature,” Jeremias says.

Less than a year later, in July 2019, Jeremias’ mother was hospitalized with a terminal illness. “During that month there were a lot of arguments about how to care for my father, who should be doing it and what we were going to do in the future, between just about everybody in the family,” he says. “All while we were coming to terms with my mom being terminal, that she wouldn’t be going home. She died on the 31st of July.”

Throughout that month, he split his life between sleeping on his parents’ couch in New Jersey and traveling back to his home in Long Island, New York. He has a beach house about half an hour from his parents’ home where he took showers and used the bathroom. “We’d made the decision to not rent out the house that summer so I’d have an accessible place to crash while I was helping my mom care for my dad,” he says.

Although Jeremias had been working with his mother since January to get his father on Medicaid, she didn’t follow through, and his father was denied coverage. Ultimately Jeremias convinced his father to reapply, explaining that he couldn’t rely on his sons to take care of him. By the end of August, the family was pretty much fractured beyond repair. “I now have two brothers who will not speak to one another and expect me to mediate between the two of them,” he says. “When this shit happens, the stress is too much for most any family to endure. With my family, the dysfunction has grown to a point that no amount of plaster or paint is ever going to be able to hide the canyon-wide gaps that have been created.”

He wishes he could support his father more, but lack of accessibility gets in the way. His brother is his father’s caregiver while they wait for Medicaid to come through, and Jeremias visits on weekends when he can. “I need to rely on somebody else to get him into my car if I want to take him out to the movies or dinner. Otherwise all we can do is sit in his house, watch TV and order take-out,” he says. “There’s really not a whole lot I can do for him alone, which is unbelievably frustrating. It reinforces my own limitations. In some ways, I feel guilty for not being able to do more for him, but at the same time it is an escape from being responsible as well.”

The shelter at home directive has kept Jeremias out of New Jersey and on Long Island with wife and son. “I haven’t seen my dad in a month, and I probably won’t see him for another two. I call him every other day or so, but he’s not interested in deep conversations, especially after the stroke,” he says. “I know his twice-a-day, Medicare-funded aides are taking care of him. My two brothers are nearby and they’re making sure he gets what he needs.”

As far as advice he’d give, Jeremias is stark. “Even situations and feelings that are completely unrelated to my parents’ aging have become tangled up into a knot that can never become unbound,” he says. “All of these insecurities and misunderstandings and feelings have become inexorably combined into a completely irrational perception of reality. So I would tell people to hash things out well before their parents die because if they don’t, they probably never will after.”

Try to Focus on the Positives

Becoming her mother’s caregiver in her final years did not come as a surprise for Janette Lawler, a C4 quad from Denver. “We’ve always taken care of each other, so I was not thrust into this position, as some are,” she says, adding that, fortunately, her mother’s dementia developed slowly the first few years, which allowed Lawler time to grow accustomed to what her mother needs as the dementia progresses.

Lawler, 54, is nearly her mother’s only visitor at the assisted living center where she lives. “Placing her there was the hardest decision I ever made,” she says. “But she’s 85 years old and very challenging due to the changes in personality and temperament that accompany dementia.”

Daughter and mother talk every day, even when it is hard for Lawler to want to make those calls. “I always try to focus on the positives, but sometimes her constant complaining gets to me and I just have to hang up,” says Lawler.

Dealing with the psychological and emotional aspects of her mother’s condition, which includes hallucinations, is understandably difficult. Lawler feels she is watching her mother slowly slip away. “We’ve been best friends my entire life, as well as each other’s emotional support, but now there’s not much to be optimistic about,” says Lawler. “I struggle with the feeling of helplessness that comes with not being able to help her to the toilet, get a sweater on or just give her a hug when she’s having a hard time. That is a huge part of the difficulty of doing this from a wheelchair.”

Although her situation is difficult, “you have to find the positives in a generally negative situation,” says Lawler, who adds that some of the positives include “living near each other so we can see each other often, the good fortune that we found a decent facility within our price range and years of mostly good memories that, with help, I am learning to focus on rather than on the frustration of the present situation.”

That’s currently a particular challenge for Lawler, as she spent the early period of the COVID-19 crisis in the hospital recovering from skin surgery. Before Lawler was discharged, her mother had reached the point where she needed to be placed in a full-time facility, and they were only able to speak by phone. “It’s been a challenge,” Lawler reported, rather emotionally. “So I’m left with phone calls and memories.”

In the end, it’s their strong mother-daughter bond that sees Lawler through. “I love my mom,” she says. “She will always be one of the sweetest and most generous people I’ve ever known. I only hope I can be as strong for her as she has been for me through all my challenging years.”

Role Reversal

When Todd Whitehead became a C3-4 quadriplegic at age 15 in 1987, his parents were his primary caregivers. But not long after his father died seven years ago, his mother acquired ALS, and he cared for her the best he could until her death four years ago. This switching of roles was difficult for both son and mother.

“When mom got ALS, we sort of reversed roles somewhat. Obviously I couldn’t provide the physical care, so I served more as her emotional support. She’d been my caregiver for close to 30 years and had a hard time giving that up,” he says from his home in Stephenville, Texas. “There were things she needed to turn over to me, now that I was going to be the main caregiver, things I would be responsible for, both for my care and hers. She also had things she needed to deal with, get off her chest and work through.”

Being cared for by her son was particularly difficult for Whitehead’s mother because she wanted to be sure he was equipped to do it all. But also, caregiving had become her identity.

“When I first got hurt, my mom assumed full responsibility for my care,” says Whitehead. He went to college, he and his parents built a house and moved in together, and their lives became intertwined. “Things went along just fine until they didn’t,” he says. “Dad got sick with Alzheimer’s and was in a nursing home for about six months before he died. And here I am, graduated from college and wanting to spread my wings a bit and be free. Then mom got ALS. I couldn’t just leave after all the years she took care of me. It was a very difficult and stressful transition for both of us.”

Fortunately Whitehead’s mo-ther had a rare form of ALS that mainly affected her throat. “In the end she was nonverbal and was unable to swallow, but she was out shopping a week before she passed,” he says.

***

Four families, four unique situations. Our parents get old, they become frail, they acquire disabilities of their own, and some of them display signs of dementia, but all of their warranties expire. Now they need us, whether they know or admit it. None of this is easy, especially as we age on wheels. But who better to figure out what kind of help and how best to deliver it? Who are we to say no or reject an opportunity to give, to give back? We need the experience of giving extravagantly.

***

When asked for advice about how to make a hard situation easier, each wheeler we interviewed was quick to offer what’s helped them:

• Take care of yourself first and find some emotional support.

• Do some senior care planning well before anticipating ever needing it.

• Be certain the entire family is on the same page about their role moving forward.

• Make sure parents are honest and not hiding financial difficulties or spending issues.

• Accept that you can only do so much because you may not always be in full possession of all the facts.

• Accept that all you can do is what you’re capable of doing.

• Do your best to maintain a sense of humor.

** This post was originally published on https://www.newmobility.com/2020/05/caring-for-your-parents-from-a-wheelchair/